The joy of feed readers and alternative ways to consume content

Let’s talk about feed readers: software that lets you subscribe to feeds to get updates when new content is published.

There are many kinds of feeds and feed readers. We’ll focus on the ones that provide the entire article from the feed, and lets you read the content directly in feed readers.

If you’ve never used a feed reader before, I highly recommend trying one out after reading this getting started guide by Matt Webb.

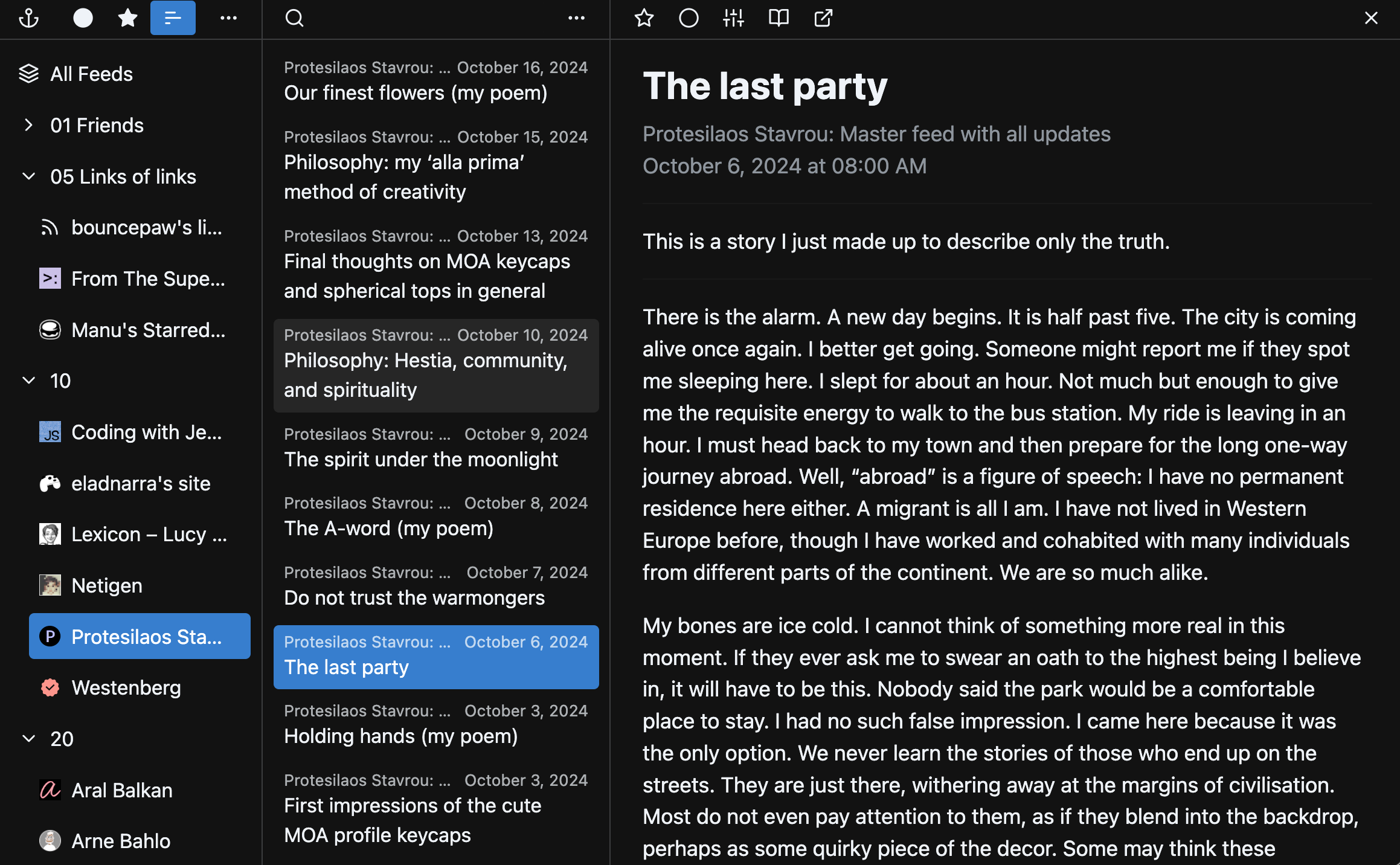

An example post by Protesilaos Stavrou in my feed reader, yarr.

There’s something magical in consuming content on the internet using feed readers.

Each of us have a list of RSS/Atom feeds we follow. Feeds from friends, from internet strangers whose blog posts you serendipitously stumbled upon and decided you want more, feeds from popular publishers and newsletters and organizations and projects you want to subscribe to for updates.

Every once in a while these feeds are refreshed and you are shown a list of new entries waiting for us to read. You select one of them and the content is displayed directly within your feed reader, in a familiar and comfortable interface. Perhaps you choose to listen to them with a screen reader or perhaps you read from them directly. Either way, the content is saved in your feed reader. It’s there, together with all the other new posts waiting for you to read and all the posts from the past you have saved.

Browsing the internet is like visiting a public library without taking the books home. It’s easy to stumble upon new books and get engrossed after flipping through a few pages. As you read them, you share the physical space of all the other readers in the library. When you’re done with the book you put it back onto the shelf for the next person to pick up. The key here, is that you’re looking at something that’s provided for you to read.

Using feed readers then, is like buying physical books and having a personal library. You pick a book from the shelf. It’s yours, you can open it, hold it in your hands and read it anytime, and put it back to your shelf together with all your other collections.

It’s like subscribing to newspapers and magazines. Each day a new edition gets delivered to you. A copy for you to read on your own as you grab a cup of coffee and make yourself comfortable on your favorite couch.

With feed readers, you get your own copy. All articles look the same when you read it from your feed reader’s reading panel. Familiar and welcoming. As you read from your feed reader, you are alone with your thoughts and the author of the content in front of you. No ads, no pop ups asking you enter your email address, no floating navigation bar covering half of the screen when you choose to zoom in. Just the content[1].

It almost feels like browsing something different from the internet entirely…

# Does this sound familiar?

It turns out, feed readers aren’t the only place you can consume content on the internet this way. Here are the few I could think of.

## Alternative browsers

How do you browse pages on the web? If you’re like most people, you might use a graphical browser such as Chrome, Firefox, or Safari.

Vivaldi, Arc, or maybe even Qutebrowser, you say? Well, all them are Chrome-based. This means websites look the same in Chrome as it does in all of those browsers[2]. There are also other graphical browsers based on Firefox or Safari.

Apart from reading web pages rendered by browsers like these, there are other ways to browse the web. And some of them lets you consume content in a similar way to reading from feed readers.

For instance, consider text-mode browsers.

As the name suggests, web pages displayed in these kinds of browsers show only text. Images are replaced with their alt text. Only some styling rules from CSS are followed, if at all. JavaScript is usually[3] not executed.

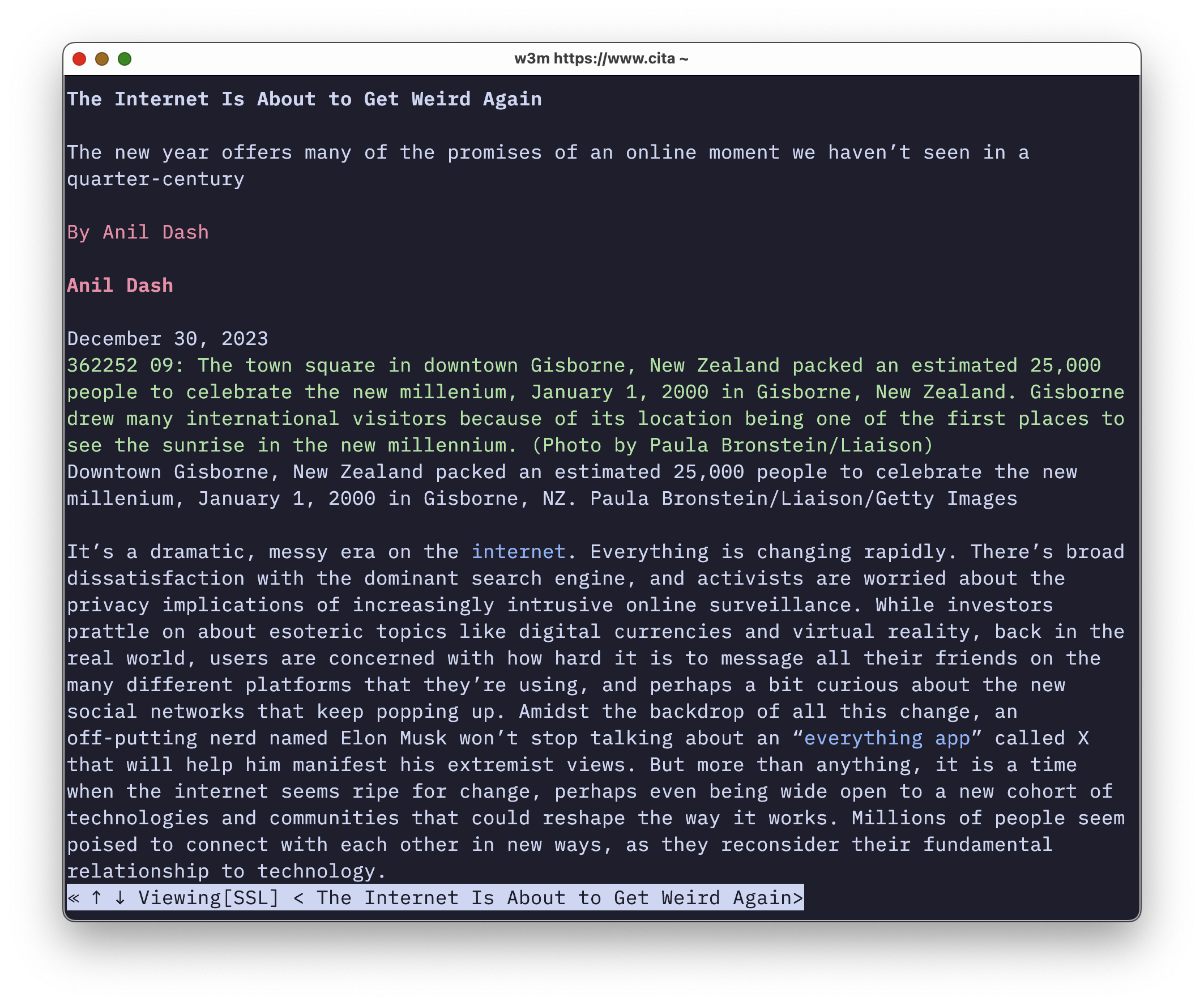

For the technically-inclined: I’m talking about TUI (Text User Interface) browsers such as w3m and lynx, accessed from a terminal.

Here’s how an example article looks like in such a browser. Text in blue are links, and text in green are alt text in place of images.

An article in w3m with mostly textual content, a few links in blue, and an image alt text in green in a terminal window.

Like feed readers, it shows just the content. Like feed readers, the reading experience is determined by the website owner. Though unlike feed readers, you can use it to browse anything regardless of whether a website wants you to.

Textual browsers are especially fit for browsing indie blogs similar to feed readers — content-focused, and less likely to contain clutter such as graphical user interface features and popups.

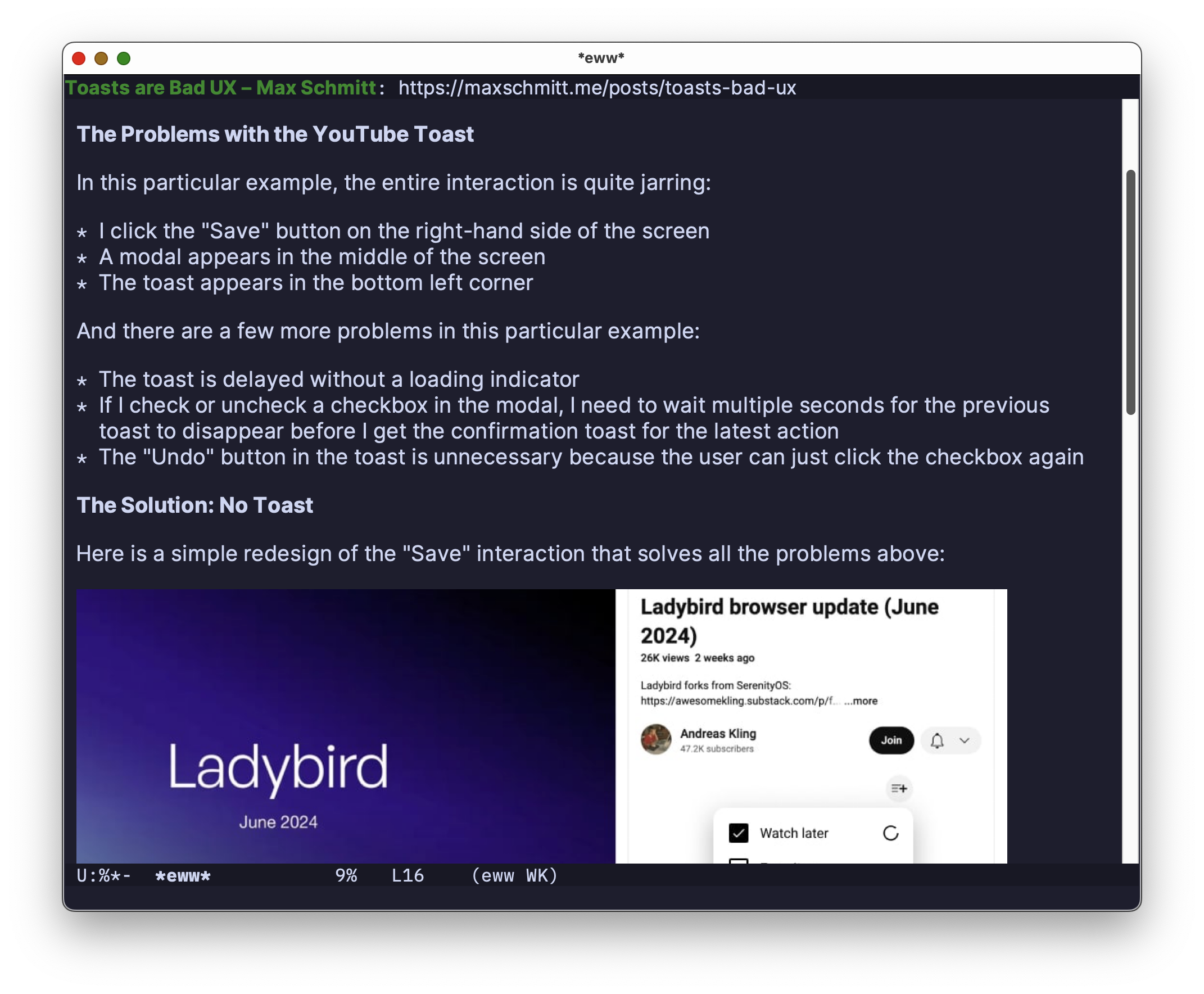

There are also browsers that display mostly text, but have support for images. One example is EWW:

An article in EWW with some text and an image.

Images and variable-width fonts are both supported. There’s a scrollbar if you want one. Hovering on links with your mouse shows the link destination. In the screenshot, the bottom half of the screen shows a cut-off image from the article. It shows what web pages might look like with no CSS and JavaScript.

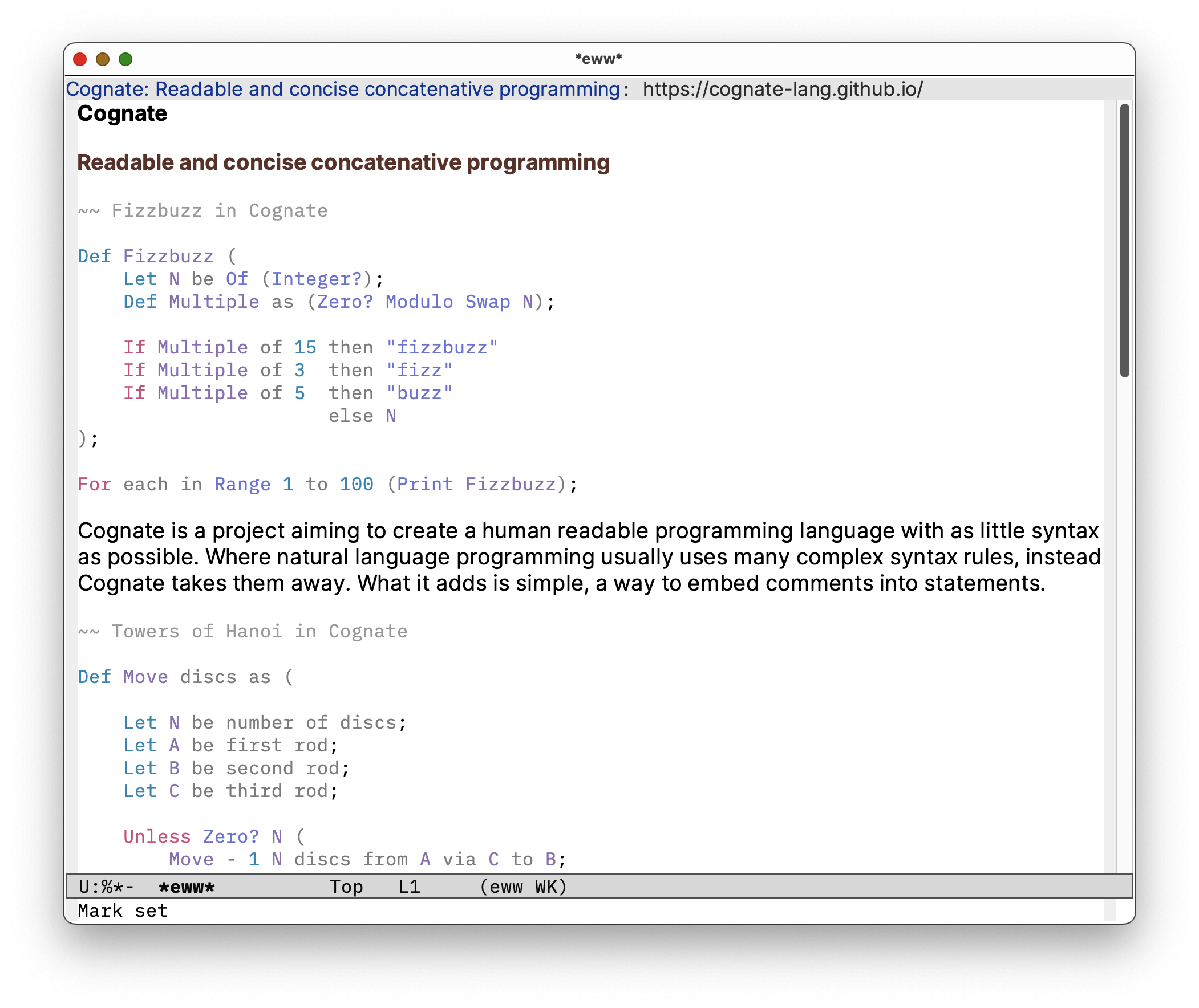

Some styles can also be rendered if there are defined inline. For example:

A page with inline styles in EWW.

In this case, text within <pre> tags displayed in a monospace font. There are <span>’s within these code blocks that have set their text color using the HTML style attribute, these colors are applied accordingly.

## Read-it-later and archiving services

Services like Wallabag lets you save links to be read later. Some makes an archive of that page so that you can read them directly within the interface in case the original resource is no longer available.

An article in Wallabag.

This is similar to feed readers in that a local copy of an article is saved and you can freely customize how it is displayed.

## The Gemini Protocol

What’s part of the internet, but outside the World Wide Web? The web we are familiar with use the HTTP and HTTPS protocols for transferring data from a web server to your browser. Content on the web is typically served with HTML.

Gemini is a different protocol. Content on Geminispace use Gemtext, a different content format from HTML. Gemtext is similar to markdown. It is extremely simple: there are only paragraphs, lists, headings, links, quotes, and pre-formatted text. Links have to be on a line of their own. This makes parsing Gemtext easy: you only have to look at the first few characters of a line to know how to render it:

# Heading 1

## Heading 2

### Heading 3

A new line introduces a separate paragraph.

=> gemini://example.org/ This text is shown for the link

=> gemini://example.org/ Here is another link

* List item 1

* List itme 2

> Here's a quote.

There is no equivalent to CSS or JavaScript. In Gemtext, there is only content. This means it is up to Gemini “browsers” to decide how a page is shown to the user, rather than the website author — everything from the the colors and font to the margins and spacing.

Here is how a page in Geminispace looks like in Lagrange, a graphical Gemini browser.

A page from Geminispace displayed in Lagrange.

Like feed readers, the user can customize how pages are displayed, and an author must opt-in (i.e., host their content on Gemini) for you to see it.

# Closing thoughts

Feed readers are wonderful. You can keep up with the latest updates from multiple sources without hassle, and catch up only when you want to, in a single, unified interface.

There are many ways to consume content on the internet apart from using a graphical browser with full CSS and JavaScript support. Sometimes, especially for non-textual content, it is best to use the browser that the website author wants you to use. Giving users the full control of a page’s style isn’t always a good idea. Other times, using different kinds of software to browse the web and the internet beyond the web can be a much better experience.

Do you use any of the method of browsing content on the internet I have mentioned? Do you know of any others?

Footnotes

Assuming, of course, that the author has made the content provided from the RSS or Atom feed complete and readable within most feed readers. [↩]

Well, not always. But do bare with me for second. [↩]

The only TUI browser I am aware of that supports JavaScript is elinks with a compile flag. If you know any others, I’d love to know. [↩]